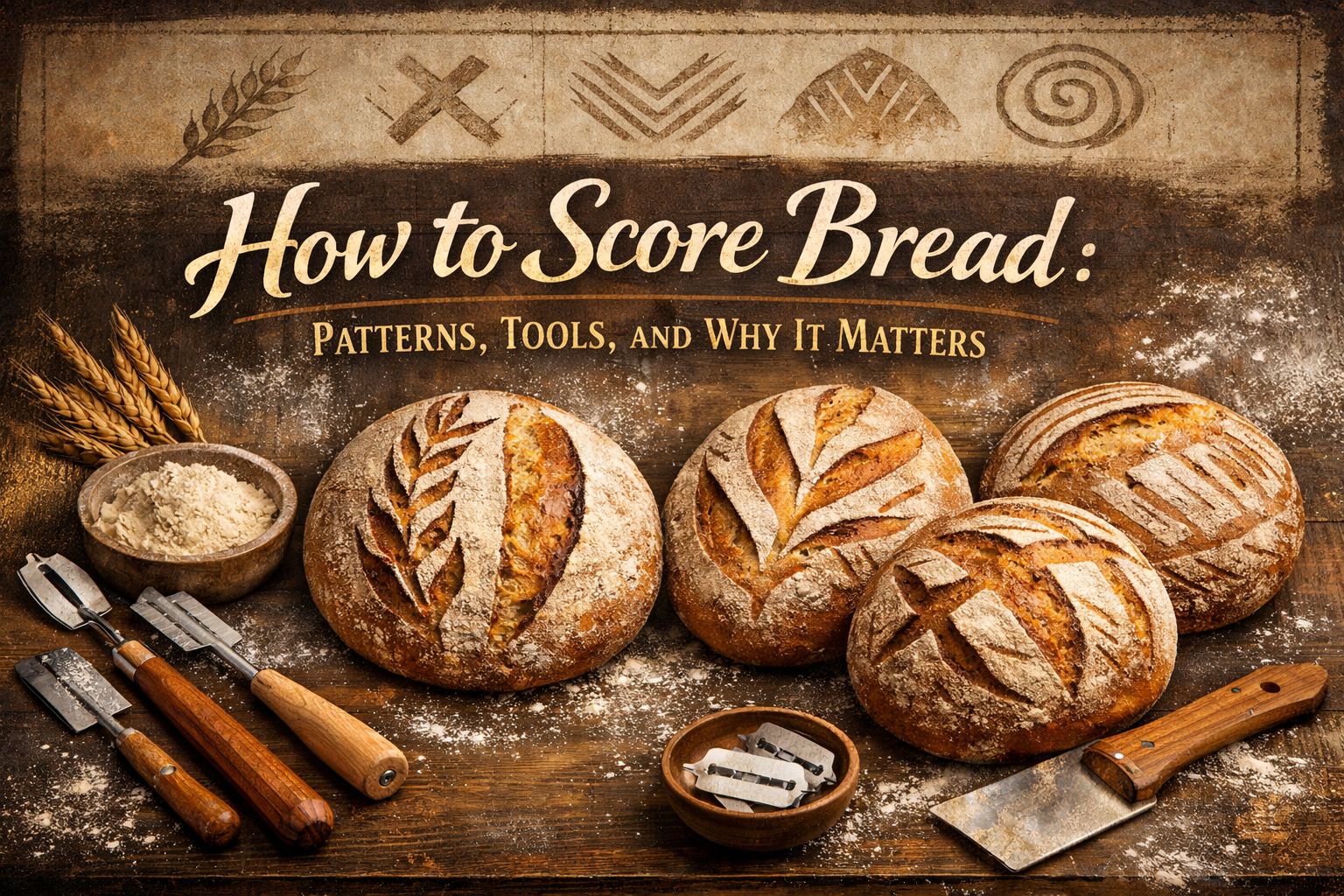

How to Score Bread: Patterns, Tools, and Why It Matters

The moment your bread hits the heat of the oven, everything changes. Gases trapped inside the dough expand rapidly in a process bakers call oven spring. It’s what transforms a dense lump of dough into an airy, risen loaf. But here’s the thing: without scoring, all that energy has nowhere to go.

The dough will still rise. But it’ll do it chaotically — tearing in random spots, opening unevenly, creating dense pockets where the crumb should be light. Scoring isn’t decorative first. It’s functional. You’re giving the dough permission to expand exactly where you want it to.

The patterns come later. First, you learn the cut.

Watch how a single confident cut controls oven spring

Why Score Bread?

When dough enters a hot oven, the yeast goes into overdrive. The heat causes carbon dioxide and steam trapped in the dough to expand violently. This is oven spring — the final burst of rise that happens in the first 10–15 minutes of baking.

Without a score, the outer crust sets quickly, trapping all that pressure inside. Eventually, the weakest point gives way — usually somewhere on the side or bottom. The result is an uneven rise, a lopsided loaf, and a crumb structure that’s dense in some areas and gaping in others.

Scoring does two critical things:

- Controls expansion. It tells the dough exactly where to open, so the loaf rises evenly and predictably.

- Creates pattern and structure. The way you score affects how the loaf looks, yes, but also how the crumb develops inside. A single deep slash creates one dramatic opening. Multiple shallow cuts distribute the rise across the surface.

It’s functional first. But when you nail the technique, the result is also beautiful — that lifted ear of crust, the crisp edges where the score opened, the way light and shadow play across the pattern you carved into the surface.

You’re not just cutting dough. You’re directing where the loaf will open, how it will rise, and what it will become.

The Right Tool for the Job

You don’t need much. But the tool you use makes a real difference in how clean the cut is, how easily it glides through the dough, and whether you can achieve that signature ear.

Bread Lame (Best)

A lame (pronounced “lahm”) is a curved razor blade mounted on a handle. It’s specifically designed for scoring bread. The curved blade makes it easy to cut at the shallow angle needed to create ears — that dramatic lifted ridge along the score line.

Why it works: The curve does the work for you. You hold it naturally, and the blade sits at the right angle without you having to think about it. Clean cuts, minimal drag, professional results.

Razor Blade

A simple single-edge razor blade works beautifully. Hold it at an angle between your thumb and forefinger, or tape one edge for grip. It’s cheap, sharp, and effective — many professional bakers still prefer a bare blade over a lame.

Why it works: Ultimate control and precision. You can adjust the angle mid-cut, make tight curves, and score intricate patterns. The downside? You have to provide the angle yourself, which takes practice.

Sharp Knife (In a Pinch)

A very sharp paring knife or chef’s knife will work if that’s what you have. The key word is very sharp. A dull knife drags, deflates the dough, and creates ragged edges instead of clean cuts.

The catch: Even a sharp knife has more surface area than a razor blade, so it tends to drag more. Serrated knives don’t work well — they tear rather than slice.

Kitchen Scissors (For Patterns)

For certain decorative patterns — like the wheat stalk design — kitchen scissors are actually the best tool. You’re not slicing; you’re snipping at an angle, creating flaps that lift during baking.

Best for: Rolls, focaccia, or any loaf where you want a rustic, textured look. Wet the blades lightly to prevent sticking.

Phase 1

The Basics

Score right before baking.

Your dough should be cold — either straight from the refrigerator or at least firm to the touch. Cold dough holds its shape better and scores more cleanly without dragging or tearing. If your dough has been sitting at room temperature, pop it in the fridge for 20–30 minutes before scoring.

Cold dough creates cleaner cuts and more dramatic ears (the lifted ridge along the score line). Room temperature dough tends to deflate when scored.

Hold your blade at a 30–45° angle.

Don't cut straight down into the dough like you're slicing a loaf. Instead, hold your blade at a shallow angle to the surface — imagine you're shaving the top layer off, not stabbing into it. This angle is what creates the "ear," the lifted flap of crust that opens beautifully in the oven.

Cut ¼" to ½" deep in one confident motion.

No hesitation. No sawing back and forth. Place your blade at the starting point, apply firm, steady pressure, and draw it through in one smooth stroke. If you saw or pause mid-cut, the dough can deflate or the edge can tear. Confidence is everything.

Think of it like signing your name with a pen — deliberate, fluid, and decisive. The blade should glide through the dough, not drag.

Start simple.

For a round boule, try a single slash straight down the center. For an oval batard, three diagonal slashes running the length of the loaf. These classic patterns look professional, control oven spring effectively, and give you room to practice your technique before moving to complex designs.

Phase 2

Common Patterns

The Cross

Two perpendicular cuts forming an X or + on top of a round boule. This is the most beginner-friendly pattern — it creates four even quadrants and allows the loaf to expand uniformly. Each cut should run about two-thirds of the way across the loaf, not edge to edge.

The Chevron

Angled slashes running diagonally down the length of an oval loaf, like herringbone or a row of arrows. Start at the top, make a cut at a 45° angle, then overlap the next cut slightly (about ⅓ of the way into the previous cut). This creates dramatic, layered ears and gives the loaf a professional bakery look.

The overlapping is key — it prevents gaps and creates that signature cascading effect.

The Square

Four cuts forming a square or diamond shape on top of a round loaf. Start about an inch in from the edge and cut straight lines to form the perimeter. The center square will rise higher than the outer crust, creating a beautiful layered effect. This pattern works especially well for enriched doughs like brioche.

The Wheat Stalk

Instead of a blade, use kitchen scissors. Cut a straight line down the center of the loaf, then make diagonal snips on either side, angling outward like the leaves of a wheat stalk. Tilt each snip slightly as you cut so the flaps open upward during baking. This technique is decorative, impressive, and surprisingly forgiving for beginners.

Wet your scissors lightly between cuts to prevent sticking. This pattern is perfect for rolls and smaller loaves.

Tips From Our Kitchen

Cold dough scores better

If your dough has been rising at room temperature, chill it in the fridge for 20–30 minutes before scoring. The firmer surface cuts cleanly and holds the pattern better.

Wet your blade for cleaner cuts

Dip your blade or lame in water before each cut. The moisture helps it glide through sticky dough without dragging. Shake off any excess — you want it damp, not dripping.

Don't score enriched doughs too deep

Brioche, challah, and other butter- or egg-rich doughs are softer and more delicate. Keep your cuts shallow (closer to ¼") or they may collapse. These doughs also don't develop ears the same way lean doughs do.

Scoring patterns affect how the bread opens

A single slash creates one dramatic opening. Multiple slashes distribute the expansion across the loaf. Experiment with different patterns to see how your dough responds — every recipe behaves slightly differently.

Practice on less precious loaves first

If you're nervous about scoring your beautiful sourdough, practice on a basic white loaf or even a batch of rolls. Muscle memory builds fast, and a few practice runs will make you much more confident when it counts.

Practice Makes Pattern

The first few times you score bread, it might feel clumsy. The blade might drag. The cuts might not open the way you imagined. That’s normal.

But muscle memory builds faster than you think. Five loaves in, you’ll start to feel the difference between dough that’s too warm and dough that’s perfectly chilled. Ten loaves in, your hand will know the right angle without you thinking about it. Twenty loaves in, you’ll be experimenting with patterns you’ve never tried before.

Scoring is the moment where craft meets art. The blade in your hand, the dough on the counter, and one confident cut that transforms both.